We live in an age that inundates us with more data than we have ever had before. And more data means better decisions, right?

Sadly, that's not necessarily the case.

Back in 2012, management consultancy CEB, now a subsidiary of Gartner, studied how more than 5,000 employees in 22 global companies used data in their decision-making.

The researchers concluded that there were three categories of workers:

- The visceral decision-makers, who followed their instincts rather than the numbers

- The unquestioning empiricists, who followed the data slavishly

- The informed skeptics, who considered the data but used it with caution

That third category—those who used data with a measure of skepticism, balancing the figures with their own judgement—ultimately made the best decisions.

How can we take advantage of the blessings of evidence without being led astray by numerical mirages?

The best place to start is with a good sense of how stats can let us down.

1. Things Change

Gathering data and learning from it can be such an effort that sometimes we cling a little too tightly—and too long—to the truths we learn. But, to put it simply, things change, and so what was true two or three years ago might not be true today.

Say you concluded a couple of years ago that your AdWords campaign would never match the effectiveness of your SEO efforts, and you just gave up on it. It might have been a wise decision then, but what if in the last three years or so the returns of paid listings vs. organic listings on search has doubled or tripled, and organic click-through rate has fallen.

So, is what you knew to be true still true?

Our changing world demands that our conclusions be periodically revalidated. Keeping your truth up-to-date takes work.

2. Past Is Not Present

It's standard statistical practice to come to a conclusion about a larger set of data by examining a smaller portion of it. Similarly, it's standard practice to use performance data from the recent past as an indicator of at least near-future performance.

For example, if you would like to project how many conversions you will get this year, it's reasonable to look at your past-year performance to use as a baseline.

However, to do that you need to make sure that there's no variable that is skewing the result during the base period you're examining. Was there a promotion in the base period? Has there been a significant price hike since then? Is seasonality a factor?

Likewise, if you are looking at data retroactively and you are trying to see whether there is a correlation between an action you took and a result, check to see whether there are any lurking variables that might have also influenced the result.

3. Sampling Error

As noted earlier, statistics allow you to come to a conclusion about a set of data from a random sample of its items. A mathematical formula that lets us calculate how likely it is that a sample will be an accurate reflection of the larger set; the output is called sampling error. (Don't worry, you don't need to do the math—online sample error calculators can do the work for you. This one is good for A/B-tests.)

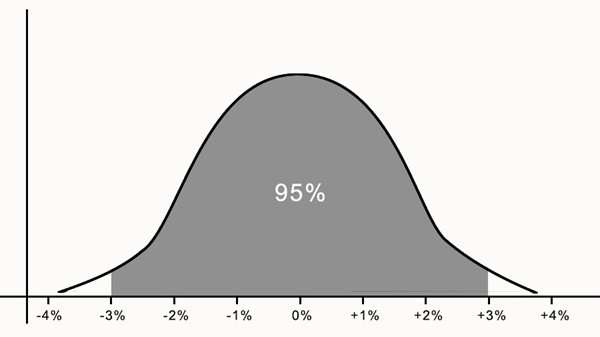

The following graph depicts a +/-3% range of sampling error, meaning that in 95 out of a 100 instances, the sampling error will be within 3%. The x-axis indicates the degree of error, and the y-axis indicates probability.

There are various common misconceptions about sampling error:

- Saying the sampling error is +/-3% does not mean that is as large as the error can be. Indeed, 5% of the time, the sampling error could be larger than 3%.

- Saying that the sampling error is +/-3% does not mean that it is as likely to be 3% off than it is to be spot on. As you can see, the probability curve peaks in the middle.

- Saying that the sampling error is 3% does not mean that is the only way the data can be wrong. This article you're reading calls out some of the other ways!

4. Unreliable Collection

In college, I used to have a job as a telephone interviewer for a major political polling outfit (which shall remain unnamed). Once, during a break, one of my coworkers gleefully told me that he had been falsifying answers as he entered them into the computer, to favor the presidential candidate he preferred. Although I shared his political leaning, I was shocked. Considering the size of the interviewer pool, that one person might have skewed the total poll results by a percentage point or more.

At night, when the pundits go on television to talk about the results of the poll, perhaps they might talk about sampling error, but it's unlikely that any of them talk about falsification.

Of course, it's not the only thing that can cause bad data. It might also be technical failure, human error, or bad protocols, too.

When you look at numbers, think of how reliable the entire process of collecting them might be.

5. Consider the Source

Sadly, numbers are often used to hoodwink us. If you're basing a decision on some data, and the source of that data is an interested party, you might want to take a closer look at—if not discount altogether—the representations being made.

6. Not Measuring the Right Thing

This is the trickiest and most costly mistake to make.

Sometimes it's made because we want to fool ourselves or make ourselves feel better.

Consider the so-called vanity metric. Is website traffic booming but conversions are flat? It's easy to emphasize the former rather than the latter. It makes you feel good and the boss will like it. It might take a rationalization, but you can manage that: "Web traffic is a leading indicator. Those people are just getting ready to swirl down the funnel!"

But sometimes we are not measuring the right thing because measuring the right thing is too hard... or maybe not even possible.

Customer satisfaction, for example, is really hard to measure accurately, even with established metrics, such as Net Promoter Score. Measures like engagement are far easier to see and record. However, which is going to be more important to the long-term health of your business?

* * *

Data can be an enormous boon, but we need to see where it is blowing in from before we let it fill our sails.