I began writing this article on November 8, after a series of interactions with Amazon.com. Two days later, a furor erupted over Amazon's sale of a self-published book titled The Pedophile's Guide to Love and Pleasure: A Child-Lovers Code of Conduct. The book has been described as a guide for how to approach young children. TechCrunch was the first on the scene with an article, followed shortly thereafter with a second article, calling national attention to the issue and denouncing the retailer's decision to defend the presence of the book under an "anti-censorship" argument. The articles triggered public outrage, resulting in a backlash via digital, social, and major media, including calls for a boycott. Unfortunately, the attention also worked to drive the self-published book to the Top Sellers list, although Amazon later removed the book and adjusted the rankings of other adult content on its site.

This article is focused on Amazon's use of social media, rather than "Pedo-Gate." However, because the incident occurred during the preparation of this article, it affected the trending and research conducted. Nevertheless, the key criticisms about Amazon's approach to social media are made even more salient in light of the recent drama.

* * *

For more than a decade now, Amazon.com has been the darling of the ecommerce world. The site has been reliable, predictable, and consistent. It has been a pioneer in the use of ratings and reviews, chapter sampling, gift reminders, wish lists, and a host of other social and practical features set the bar for online shopping. Amazon has offered great user and customer experience, from the Web interface to its call center face-to-face discussions.

It would be a disservice not to point out that Amazon was a game-changing leader in social commerce well before the social media frenzy and hype of the past several years.

But the Playing Field Has Changed

Today, the site-driven "rating," "tell-a-friend, "add to list," or "write a review" are commodity functions found on any good shopping site. On the Internet, the standalone Web presence is giving way to the networked economy, as interactions and transactions scatter across multiple hubs. Websites are now interconnecting via open source or open API to other sites, tools, apps, networks, and communities. People don't just interact with people, products, and brands, they like them, follow them, and friend them—forming tangible relationships—without leaving the digital space they're in.

When it comes to shopping, products are accessed, sorted, compared, reviewed, rated, and purchased across sites, browsers, platforms, and devices with relative ease. An increasing number of websites leverage embedded site features and services such as Facebook, Twitter, You Tube, and others. These help people interact, explore, discover, investigate, compare, check in, recommend, purchase, and give easily—regardless of the site, access point or platform used.

With such changes come increased expectations. People expect extensibility, simplicity, and the presence from the brands they trust. They also believe that when they run into questions, issues, problems—when they need help, support, or just a little love—the brands they trust will answer... because people matter and because the brands care.

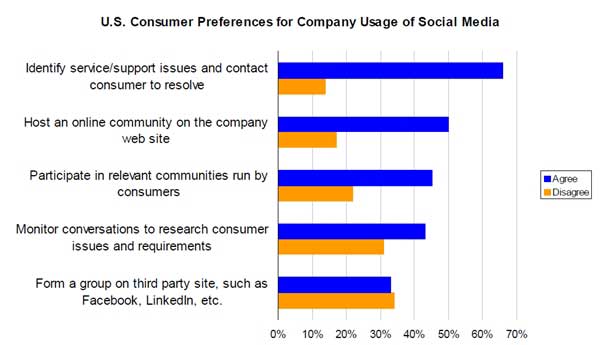

Consider this chart from a CustomerThink July 2009 Consumer Survey, which provides a snapshot of consumer expectations of company use of social media.

Amazon Promotes, but Largely Fails to Serve

At arm's length, Amazon may look socially engaged. When it comes to its own .com presence, this may be somewhat true. However, it's important not to mistake the presence of some social-sharing options on its product pages, a few Facebook fan pages, and a host of Twitter accounts for active or effective engagement in social commerce. When one looks a little harder—past the accounts and landing pages—and does a little analysis on message streams, some important and consistent anti-social trends emerge.

On Twitter

On Amazon's main Twitter page, the first thing one may notice is that Amazon calls it an official "Twitter Feed." Unfortunate as this terminology may be, it is indeed, a feed: The posts are broadcast-driven, self-promotional messages. Amazon does not respond to replies or appeals for assistance. Retweets and @responses of any kind are sparse, limited to positive mentions only, and mostly exchanged with "celebrity" entities (authors, actors, musicians, etc.). Furthermore, the only accounts Amazon follows are other Amazon accounts and a few (obvious or not) employees. In short, there's little relationship, and virtually no consumer dialog or customer service.

The same holds true for 14 other Amazon Twitter accounts, like Amazon Videos, Amazon Games, Amazon Deals, although each account follows different types of people (e.g., Amazon's Music Account follows a few musicians, and AmazonVideo follows directors, entertainment venues, and industry pundits). Most Amazon accounts display a pattern of a very skewed ratio of those it follows and those who follow it, and a tweet history that reflects a lack of both interest and activity in responding to @ inquiries and messages.

The only exception seems to be the Amazon Wish List Twitter account, which seems to have a heart with regard to answering people's questions about Amazon's browser-based shopping extension. This account has even referred people to 800# customer support for service-related inquiries. While a hopeful sign, unfortunately the bulk of the activity here is to drive use of the shopping extension to promote and drive sales. This is the path of least resistance in social media: meeting nominal and noncontroversial "points of need"—rather than providing critical customer service and support. (Points of need, as defined for this article, are individual mentions, comments, or messages that express the need for a brand's attention, consideration, action, or response.)

Amazon's pattern of nonresponse to point-of-need mentions becomes even more visible when one conducts a Twitter search for Amazon customer service. Prior to the scandal, we noted a significant number of unanswered customer service inquiries, in addition numerous positive mentions.

With the scandal and volume of messaging that occurred recently, search results are only now going back to normal. However, the type of point-of-need requests ranged from general questions and inquiries to praise, complaints, recounting of poor experiences, and direct order or issue inquiries.

On Facebook

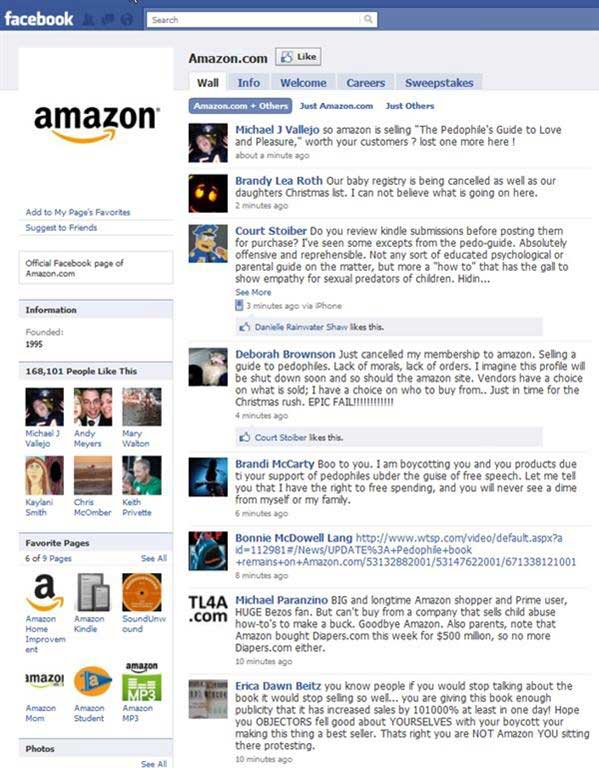

Conducting a search for Amazon on Facebook reveals a very large list of Amazon-related pages, groups, and personas. Amazon's official Fan Pages are not listed as official... so it can be hard to distinguish them from a ton of bogus Amazon pages that also use the Amazon logo and have hundreds or thousands of fans, none of which could possibly fit in the screen capture shown here. (Over the period of one week, reviews were conducted of verifiable Facebook Pages, including Amazon's main account, Amazon Kindle, Amazon MP3, Amazon Affiliate. (Reviews of posts on Fan Pages were conducted before and after Pedo-Gate, on Nov. 9, Nov. 10, Nov. 11, Nov. 16, and Nov. 17.)

The primary Amazon Fan Page has just over 240,000 fans. The default view for the Wall shows only Amazon.com posts. Amazon status updates usually garner at least 30 comments, reaching to the potential for hundreds of comments per post. Responses to comments were noted only as an extremely rare occurrence, and only on one Fan Page. Just prior to the scandal, at least 10 unanswered customer service issues were noted during a cursory review of comments posted on Amazon's main fan page. Such issues became more noticeable with the default setting for the main wall set to display wall posts from Amazon + Others. During the scandal, wall posts and comments skewed heavily negative and were often profane. More recently, wall posts and comments seem to be skewing more positive. However, crisis aside, we found consistent placement of unanswered point-of-need mentions during the review period. In addition, we found a significant amount of spam posted on the pages. On the Amazon Associates Fan Page, the proliferation of spam was very high.

The Amazon Kindle Fan Page also suffered during the scandal, although the page is typically characterized by largely positive user feedback from loyal customers. At the same time, beyond "crisis related" comments, a number of direct questions and inquiries about the product, features, and functionality were noted here, also with no noticeable Amazon response. There were a number of complaints about bugs with the Kindle-A-Day Giveaway contest with no response, such as this:

A slightly less dim spot was the Amazon MP3 Fan Page, where free MP3s and daily deals are presented for fans. There, a very limited number of responses to user comments were noted. However, those were focused at nominal point-of-need sales-based issues and did not pertain to any critical point-of-need issues, especially related to the scandal.

In general, the types of user comments on Facebook vary from post to post and include everything from post interactions, kudos and praise for the retailer, complaints, customer service inquiries, comments about products, and affiliate-related issues. Some posts became more of a "magnet" for negative feedback than others, such as Amazon's "Kindle-A-Day" status update on Amazon's main Facebook page. However, public ire and other legitimate customer service requests or issues seemed to be scattered in comments and posts across all Amazon's Fan Pages.

Other than two MP3 responses, we noted no discernable response related to audience questions, comments, or concerns. We also noted no blanket response via status updates directing people to proper channels for service and support, or offering an official response to the thousands of users who complained about the pedophilia book during the crisis "window."

In general, it seems Amazon's practice is to post promotional messages to solicit mass response and then summarily ignore those responses—even if people are requesting a response or help. Also, although keeping on top of spam on a Fan Page can be a challenge, Amazon does not seem highly concerned about illegal use of its logo or the posting of spam on its official pages.

Total Volume of Point-of-Need Inquiries

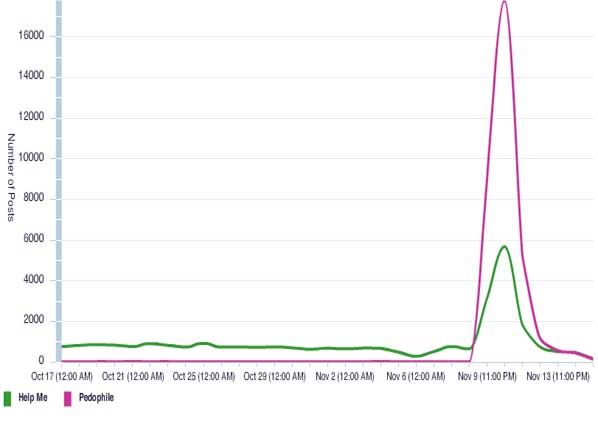

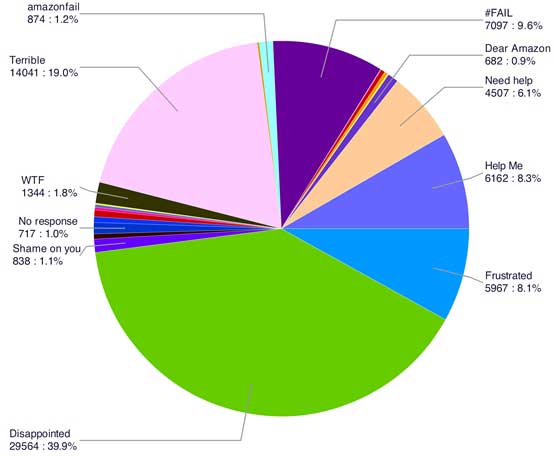

Of course there's more to social media than Facebook or Twitter. You can google any number of terms and excavate blog posts, message board posts, and "mentions" related to unresolved customer service or challenges with Amazon customer experience. Manually sifting through the high volume of mentions, posts, status updates, etc. is difficult, however. So, in an attempt to get a handle on the volume of point-of-need mentions, Radian6 assembled a high level, 30-day report on point-of-need mentions.

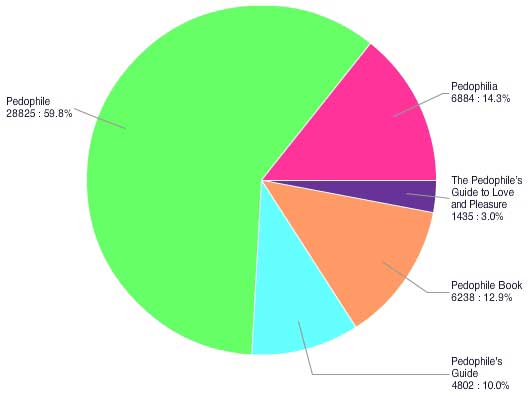

In fairness, we attempted to separate a more general set of point-of-need mentions (in green, below) from mentions specifically mentioning pedophile book crisis (pink). However, it's difficult to do so with any kind of surgical precision using natural language query. The numbers do serve as a useful point of reference in determining potential volume, however.

In summary, by Wednesday, Nov. 17, Radian6 identified 72,964 potential point-of-need mentions over the course of 30 days, with 35,535 related specifically to mentions of the pedophile book. Even without an active crisis, it appears that Amazon is ignoring hundreds of potential point-of-need mentions per day.

The queries are based on natural-language queries using an array of commonly used terms, and the nuances of each mention mean the results are not 100% conclusive. That is, the mentions tallied may skew positive or negative, and may not reflect direct service related issues or complaints. Mentions may include praise, simple statements or general comments, and may be repeated mentions (e.g., retweets) of a single mention. However, analysts did apply queries that would be more indicative of a direct expression of need, an open issue, or a lack of resolution, such as like "Help me," "Need help," ""Frustrated," "Disappointed," "No Response," "#Fail," and "Amazonfail," in addition to "Dear Amazon" (which tends to trend toward a point-of-need mention). Looking at the curves, there is some potential overlap between the "categories" of mentions. For example, it may be likely people who complained specifically about the book may not have not used the word "Pedophile" related terms but may have used a term from the other query, such as #amazonfail.

Here is some more detail on both queries:

Point-of-Need Mentions Related to Help and Service

Point-of-Need Mentions Related to the Pedophile's Guide to Love and Pleasure

Applying Some Basic, Common Sense

Essentially, it seems well established that Amazon doesn't use social media to handle, forward, respond to, or manage customer-service issues. In fact, Amazon's position on its use of Twitter, specifically, is that Amazon is looking into ways to use Twitter more effectively in the future. In the meantime, the company underscored that social channels are not recognized venues for customer service or support, and people must call or email to obtain help.

When one considers the sheer scope and volume of these point-of-need mentions, and the cost and complexities of integrating this additional "load" from foreign platforms (not Amazon Web Services based response), it's easy to understand, at least in part, where Amazon is coming from.

At the same time, there's an amount of common sense that is missing in Amazon's approach. If Amazon does indeed have a "no service" policy in social media outlets—Why not place disclaimers or directives within these destinations to explain this position? Why not offer direction, and point people to channels for service and satisfaction? Instead, Amazon leaves people hanging.

Furthermore, remaining mute and unresponsive in a crisis situation seems ill informed. On Wednesday, Nov. 16, at about 10:45 pm ET, CNN reported that Amazon had removed the controversial book from its site. Due to caching issues, however, the thumbnail image and description could still be found the following day. On Thursday, Nov. 17, Amazon faced additional backlash from lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender audience as well as anti-censorship pundits over the de-ranking of an array of "adult" titles.

None of these developments was followed by any official Amazon response—not on Amazon.com or any media outlet.

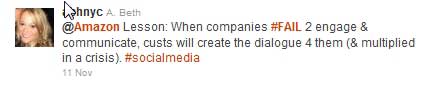

In contrast, the best success stories in social media prove that success is driven by strategically extending businesses, using the tools to improve customer experience in meaningful and valuable ways. If great customer service is a key component of Amazon.com's success, then it logically follows that company's extension into social channels would include service and response at some level. Beyond the sales that may be driven by these digital venues, Amazon's failure to engage and serve users lack of social engagement with users here may very well be working to undermine good customer experience.

Anticipating, Listening and Responding to People's Needs

Amazon has always demonstrated the ability to anticipate and respond to user needs, even applying innovation and invention to better serve. Unfortunately, in social media, Amazon doesn't make the grade. Perhaps the company has become so "platform focused" that it has developed blindness to the important changes occurring in ecommerce. While it figures things out, people—customers—are talking a lot! They're talking about the crisis as well as other aspects of Amazon's customer experience, and others are talking back. The lack of participation in this dialog doesn't just equate to missed opportunity for Amazon, but can actually result in the exacerbation of issues.

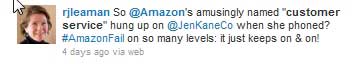

For example, following the Twitter stream during the pedophile book crisis, several people complained about being summarily disconnected when calling to complain about the pedophile book. Whether this happened to 10 people or 1000—and by mistake or intentionally—when people "hear" the same story repeated, they are likely develop the assumption that Amazon was hanging up on many people.

Incidentally, a quick review in Radian6 on terms like "hung up" showed incidence of mentions related to being hung up on, or disconnected, represented a very small portion of overall mentions. Nevertheless, while they are not always based on fact, perceptions may well become the reality in which people reside—and respond.

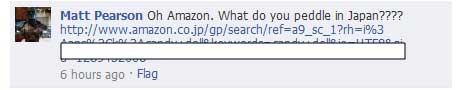

Furthermore, when brands fail to engage with concerned people, they leave a highly motivated, passionate, and connected audience to speculation. These audiences can be far more resourceful than a brand may like. They often compare notes, do additional research, answer each other's questions, provide links and other materials... and they sometimes uncover material that may be further damaging, and share it. Here is one such comment from a post in Facebook, which leads to some equally controversial content from Amazon Japan (link and content disguised so as not to promote the product):

Ultimately, the unanswered masses have the tendency to "out" brands by fanning the flame of controversy, speculation, and outrage. As one user aptly put it:

The lesson? Responding carefully in a crisis can direct people to outlets where they will feel heard, clarify factual information, request patience while issues are investigated, and generally demonstrate a proactive, caring stance. It's essential to listen, anticipate, and respond—especially on sensitive issues. Otherwise, backlash may continue to escalate.

The Cost of Being Anti-Social

Without question, Amazon has chosen to view social tools as broadcast mediums. Despite an impossible-to-ignore proliferation of celebratory, highly positive mentions on the social grid, Amazon's anti-social use of social media is working to perpetuate negative exposure and breed distrust and even public contempt. It is also resulting in the proliferation of hundreds, if not thousands, of unanswered daily point-of-need mentions.

A one-time agile company, Amazon has failed to strategically use social channels; that failure encourages the perpetuation of a lethargic, sales-driven corporate culture that fails to...

- Listen

- Apply critical thinking

- Empower staff to respond

- Acknowledge and correct mistakes

- Salvage at-risk relationships

- Embrace the value of people

Its approach can do nothing but create a cycle of disservice and dissatisfaction, especially as stories of poor customer experience spread across the social grid.

With regard to the pedophile crisis, on Facebook alone a cursory review revealed more than 12 Fan Pages titled "Boycott Amazon" with more than 27,535 fans combined (the largest had over 16,300 members) and at least 30 "Boycott Amazon" Groups with a total of some 1,500 members objecting to the book alone. Additional groups and pages support Amazon (albeit they have a weak following) or to protest the re-ranking of "adult" content. Ultimately, the third and fourth-quarter performance at Amazon will reflect the true impact of the crisis.

But perhaps what Amazon has lost is nothing compared with what Amazon stands to gain by correcting its social-media problem. There is so much potential up-side for Amazon as it extends strategically through social media, from the ability to sell to loyal, engaged audiences in a more targeted manner, to serving the needs of audiences in frequently accessed channels.

To course-correct, Amazon would do well to examine the social media approaches of companies like Zappos—a company that Amazon owns—in addition to Dell, United Airlines, Comcast, BestBuy... and a host of others now using social media to strategically extend their businesses and drive better customer experience.

When Amazon does pull its head out of the virtual sand to demonstrate active listening and response on the social grid, it will enter into a new era of true social commerce—and help open the doors of potential for more greatness for the retail giant.

In the meantime, like the pesky caching issues that slowed the removal of the controversial book from the site, Amazon will be hard-pressed to erase the emotional toll of the scandal itself. The digital "remnants" of the crisis won't fade into the background soon, especially with the extensive media coverage and response Amazon has received. In the end, people will be forced to choose whether to purge their own "personal memory caches" to again shop with Amazon.com.