A brand manager's job is to develop and propagate a brand's identity—the core meaning that the brand managers want the brand to convey.

But the customer is the one who has ownership of the brand image, because it is the representation of the brand in the consumer's mind. The brand image is created penultimately through marketing communications, but ultimately through the consumer's experience with all the brand touchpoints. That experience includes the synergistic or atrophic effects that individuals have with other users of the brand.

Therefore, the ownership of the brand image is not totally under the control of the marketer. Brand image is the sum of the meanings that customers actually perceive in their relationship with the brand.

Sometimes brand identity and brand image are perfectly overlapping. That occurs when the customers perceived brand image is exactly what the brand managers intended when crafting the brand identity. Although that is the ideal, often the brand identity and brand image are skewed. The degree of the skew can be minute, or vast.

In a sense, marketers are less like a typical puppeteer, pulling the marionette strings of the brand—and more like Gepetto, crafting a brand that takes on a life of its own. As brand managers, we design the core of the puppet. But the market breathes life into the brand, which like Pinocchio takes on its own character.

In the extreme case, your brand image might not only be skewed from its identity but also adopted or "hijacked" by totally unintended market segments. Imagine that you decide to throw a formal party and most of the people who show up are party crashers. Was your party a success or failure? Well, that depends on the intended purpose of party.

Likewise, in brand management, there are times when we craft a brand identity that targets a specific market segment and everything progresses smoothly. Then one day an unintended market segment decides to hijack your brand.

Blessing? Curse?

Is brand hijacking a blessing—or a curse?

As is true of just about every marketing question, the answer is, "That depends." A better question might be, When does it matter whether your brand is hijacked or not? Let's look at this question first.

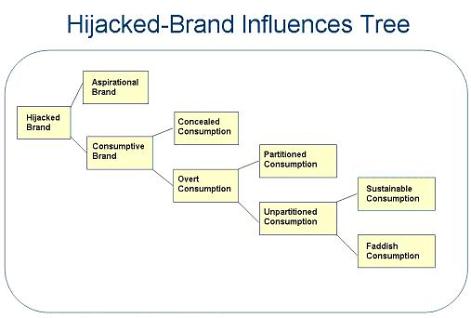

For most market segments, brands can be classified into "aspirational" brands and "consumptive" brands.

Aspirational brands are those that are coveted by a certain set of customers, yet they are out of reach for them. An example would be a Lamborghini or a Maybach car. They represent "brand dreams" for most people, as only a small percentage of the population can afford one. A Maybach is priced starting at $315,000. The company, a Mercedes-Benz division, sold only 500 of the cars worldwide in 2004, with half of those sold in the US.

This is a miniscule percentage of the overall car market, yet just about everyone who watches MTV knows the Maybach brand. Is this brand hijacking of the Maybach brand a precarious situation for Mercedes-Benz? Not at all. When it comes to ultra-luxury, there's usually no harm in having more people know that your brand's customers have got the ultimate bling.

A consumptive brand, in contrast, is a brand that is actually consumed by a market segment. These brands can fall into either the "covert" consumption category or the "overt" consumption category.

The brand usage of a covertly consumed brand is opaque to other consumers. Video games are usually covertly consumed, for example. If you launch a brand of video game targeted at kids, but it is adopted by young adults, there is usually no adverse effects for the kid market. The only kids that might be put off are those who would not be caught alive playing the same game as their parents.

Overt consumption of brands occurs when brand usage is transparent to other consumers. In this case, the user identity becomes part of the brand image. When a certain market segment uses a brand, the brand consumption may be either partitioned or unpartitioned.

With partitioned consumption, a brand is used in situations where other market segments are separated from the consumption experience. For example, when rappers rapped about Tanqueray gin, its popularity spread beyond the traditional Anglo-Saxon gin-and-tonic crowd. Since the consumption of Tanqueray at rap events is definitely segmented from its typical consumers, the brand hijack is a more of a blessing than a curse. It just extended into a new market with essential vitality, while retaining a hold on the original market.

For some brands, the consumption of the brand is unpartitioned: When one unintended market segment latches onto your brand, the traditional market segment that previously owned the consumption brand, as well as unpenetrated segments, become widely aware of the brands' new consumers. With unpartitioned consumption, the usage of the brand by the new market segment (along with the user imagery evoked by the new users) results in a shift in the brand image.

Should new users of the brand be encouraged when there is unpartitioned consumption? This is a tricky question. The brand manager has the precarious job of deciding whether consumption by this new group is attractive. The brand manager ultimately needs to determine what effects will occur through inter-segment interaction, and subsequently what effect that will have on the financial performance of the firm.

Part of the job is to figure out whether the consumption pattern is faddish. If a new segment hijacks your brand, changes the brand image, and then shortly thereafter drops it for the next big thing, it would be unwise to support that new market segment. However, this is not so simple a question; the faddishness or sustainability of the brand can be influenced by efforts of the brand manager.

Even if the consumption is sustainable, it is up to the brand manager to decide which market segment to pursue. Of course the right segment to pursue is an economic question. The brand manager needs to decide which segments are best for the wellbeing of the organization.

Cancun, a resort city on the Caribbean, has been facing these questions. It is becoming associated with wild and crazy Bacchanalian spring breakers overloaded with beer, tequila and hormones. Although the spring break crowd represents only 1% of visitors to Cancun, the city's image is becoming dominated by crazy-collage-crowd imagery, which is disseminated widely via television. Cable channels providing in-depth coverage of the revelry include MTV and E! Entertainment.

Cancun is worried that these brand hijackers will adversely affect the choice of travel destination by the more lucrative newlywed, golfer and eco-tourist segments. To counter the hijacking, the city has launched a Civility Pact, a code of public behavior designed to limit overindulgence by the spring break crowd. The police will patrol bars, clubs, and elsewhere to keep festivities from getting out of hand, and the city hopes such efforts will reduce its attractiveness to the college crowd, and reduce its 40,000 spring breakers to more manageable numbers.

Conspicuous unpartitioned consumption is not always a bad thing. Corona beer was first brewed in 1925 by Cerveceria Modelo and was imported into the United States in 1979. Clearly, between 1925 and 1979, Corona was a Mexican beer for Mexican people. As the story goes, surfers from California discovered Corona back in the 1970s. Usually served with a wedge of lime, the brand became associated with escape, instant beach in a bottle. This helped propel consumption of Corona in the US, and in 1997 it surpassed Heineken as the number-one imported beer. It can now be found in over 150 countries and is the fifth-best selling beer in the world. Clearly, this hijacking by surfers in the 1970s was a blessing for Grupo Modelo (as well as Anheuser-Busch, which owns 50% of the company).

Ocean Pacific (OP) is another hijacked brand. This time, the brand originated in the surfer market, in the 1960s, as a surfboard label. In 1972, the brand was extended into a line of clothing, starting with surf trunks and walk shorts and later with Hawaiian shirts. In 1977, OP started to sponsor the Association of Professional Surfers, and its brand became not only synonymous with surf culture but also the clothing of professional surfers.

In the 1980s, with surf culture becoming mainstream, OP became a household name and was sought out by surfers and aspirational surfers, skaters, and snowboarders. Things went well for a while, but in its accelerated growth the brand managers lost the mystique of the brand. The company started mainstreaming its distribution, selling through "uncool" places like Kmart. At the same time, the market for surf clothes became populated with a plethora of competitive brands. As a result, OP sales slumped for a decade. It wasn't until 1998 that a new management team revitalized the brand by reconstructing a promotional team of athletes, musicians, and celebrities to carry the OP torch.

From Hijacked to Smooth Landing

So, what have we learned? There are some simple rules when it comes to your brand being hijacked:

- If your brand is an aspirational brand, let it be.

- If your brand has concealed consumption, promote to the new segment.

- If your brand has partitioned consumption, promote to the new segment.

- If your brand has sustainable unpartitioned consumption, weigh the benefits of supporting the new segment with impact on your original target segments. However, keep in mind that you do not totally control the brand. Unless you can enforce policies (like the government did in Cancun), your potential for dissuading a new segment from desiring your brand could be as hard as keeping moths away from bright light.

Remember, if you decide to pursue the new market segment, you cannot force a round peg in a square hole. You will have to totally rethink your strategy and quite possibly pursue new value propositions, distribution channels, communication, and pricing strategies.

Bibliography

- OP History, https://www.op.com/history/, accessed April 18, 2005

- Smith, Geri and Lauren Gard, "Life's a Beach for Corona," BusinessWeek, Feb 7, 2005

- "A Break from Spring Break," The Economist, March 10, 2005

- Jette, Julie. "Selling Luxury to Everyone," https://hbswk.hbs.edu/pubitem.jhtml?id=4759&sid=-1&t=special_reports, accessed April 18, 2005