At the turn of the 20th century, a limited number of products and services were available to most consumers. Most products were produced and delivered locally. Merchants knew their customers intimately; many were friends and neighbors. While modern marketing was still in its infancy, merchants intuitively practiced what would later be coined the four Ps of marketing: product, price, place, and promotion. Due to the personal relationships merchants had with their customers, frequently their loyalty was obtained. If the customer had an issue with the product and service, the merchant would likely fix the problem on the spot. If the merchant had an idea he wanted to get feedback on, he would simply talk to his customers, face-to-face.

In this model, while the consumer did receive highly personal service, frequently leading to loyalty, the driving force in the relationship was the product/service company. Let's not forget Henry Ford's famous quip—that consumers could buy a Ford in any color they want as long as it was black.

At the turn of the 21st century, the dynamic is just the reverse. The large consumer product, service, and retail companies—none of which know their customers personally—hold the vast majority of market share in most every category. These "category killers" offer an array of products and services that far surpass anything that could have even been imagined a couple of decades ago—let alone 100 years ago. Sophisticated branding, promotion, advertising, and product innovation have created a plethora of choice for consumers—from the different companies they can choose to do business with, to the array of specific products and services. Retailers are open for business seven days a week, banks are open on weekends, and the Internet enables commerce and customer service to take place 24/7. And, many of these companies offer consumers the opportunity to enroll and participate in their loyalty programs.

A rational person could be led to believe that a seemingly endless choice of products and providers, increased service hours, unprecedented access and convenience, coupled with loyalty programs, would lead to consumers being more loyal than ever. However, the result has been just the opposite—much to the chagrin and frustration of marketers.

Intense competition, aggressive pricing, and a multitude of product choice and inconsistent service are resulting in customer loyalty declines in most every category. This challenging dynamic is intensified as consumers are bombarded around the clock with promotional offers and messages through the media. Due to this combination of factors—it is the consumer that holds the reigns of the company/consumer relationship in the 21st century. Can you imagine how Henry Ford's attitude about the consumers' choice of car color would be received in 2005?

Over the past two decades, in an effort to stem this continuing trend, there has been a proliferation of programs initiated by consumer product, service, and retail companies in an effort to achieve greater degrees of customer loyalty. Companies in just about every industry have a loyalty program for some segment of their customers, and many companies not yet engaged in a loyalty initiative are actively considering it.

There are two reasons for this. First, the customer loyalty dilemma cannot be compared with the many business improvement fads that go almost as quickly as they come. Second, customer loyalty (or the lack thereof) is a long-term issue that will only become more challenging over time, not less.

Turning Customers Into Advocates

While some companies are seeking to simply get their customers to buy more over a longer period of time, some enlightened loyalty marketers are raising the bar. They are seeking to transform as many of their customers as possible into "advocates" for their products and services as research consistently shows that word of mouth promotion is always the most powerful and persuasive.

Taking a customer to the "advocate" stage in a commercial relationship is very challenging, but it delivers enormous promotional and economic benefits to companies that achieve it.

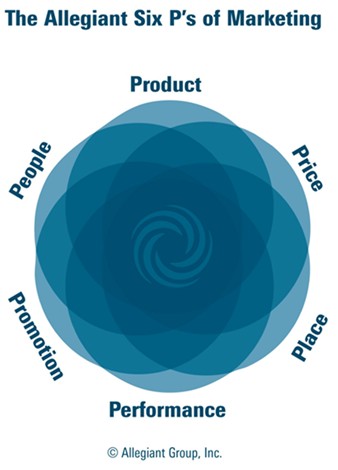

The Four Ps Plus Two

To move toward transforming customers into advocates, companies need more than an attractive, well-executed loyalty program. Many companies initially engage in customer loyalty with the best of intentions—but with a fundamental misunderstanding of what a loyalty program can and cannot accomplish. Unfortunately, many companies see the creation of a loyalty program as the panacea for endemic customer turnover, churn, and dissatisfaction. This wish couldn't be further from the reality of what these programs can reasonably be expected to achieve.

The truth is, I have never encountered a loyalty program—no matter how well executed—that can overcome a company's inability to execute consistently on the four Ps of marketing: product, price, place, and promotion.

Loyalty programs cannot make up for major operating deficiencies in an enterprise, nor can all the data from a sophisticated CRM platform. That is why, in this new customer-centric environment, my experience has led me to conclude that companies should add two more Ps to their marketing mix to effectively engender customer loyalty.

The Fifth 'P'

The fifth "P" is people. It is perhaps the most challenging part of the loyalty equation and one of the most important. People have a profound affect on customer loyalty as employees, distributors, or franchisees of an enterprise—and it has been proven that people are a powerful part of the customer loyalty equation. Their knowledge about the product or service, their friendliness and approachability, their motivation and dedication to serving the customer are all tied directly to a company's ability forge a lasting, profitable relationship with its customers

It is no surprise that some companies with the lowest turnover of employees have the lowest turnover of customers—making them the customer loyalty leaders in their category. This issue will become increasingly challenging for companies as employee loyalty declines and an increasing amount of work is sourced to third-party providers.

Managing the people equation effectively cannot make up for an inferior product, but it is often the intangible asset that becomes the reason why customers buy from you and not your competitors—even when there is product parity and similar pricing. In some instances, having quality people within an organization and its outsource partners—and the way they perform—can enable companies to charge a premium for goods and services as result of effectively optimizing their human resources.

The Sixth 'P'

The sixth "P" is performance. Performance is the total customer experience as affected by product, price, place, promotion, and people. While each of these is important in its own right, how all these activities combine in harmony is what matters most to consumers.

For instance, if one has a unique product or service that is priced right, promoted well, and distributed effectively—is that enough to effect customer loyalty? The answer is likely no. If the company is doing all these things right but customer service is poor or staff members are rude—in the eyes of the consumer the product/service will not have "performed" to their expectations.

The first four Ps are critical to loyalty but individually, they are only parts of the puzzle. When the objective is loyalty and advocacy this can only be achieved through performance as perceived and judged by the customer.

Critical Success Factors

Companies that are executing the six Ps in an effective manner can likely achieve further improved customer retention, incremental spend, and financial yield from customers through a well-constructed loyalty program.

The ultimate success of any program is highly dependent on thinking through the critical success factors during the strategy, planning, and design process. To create a program that is both meaningful for the consumer and profitable for the sponsor—clarity must be achieved resulting from significant discussion, analysis, and ultimate executive management support and buy-in.

By its very nature, loyalty management is a long-term strategy, and any program resulting from such a strategy will require significant organizational support, resources, and emphasis from the most senior members of the management team.

Strategy and Economics

In effective customer-loyalty management, strategy and economics are inextricably entwined. There are two reasons:

- First, management can only rationally support a loyalty strategy if the financial outcome to the company is clearly favorable.

- Second, the economic reality of the organization provides certain opportunities and restrictions to the strategic approach employed. What is the primary mission of the program? What customer behavior is the program seeking to affect? Is the program intended only to engage and reward its best customers, or is the intent to manage the migration of customers from the least frequent to the most frequent? These decisions are central to understanding what the primary mission of the program will be.

An empirical understanding of customer profitability dynamics in essential: What is a rational investment in order to achieve the desired customer behavior? What degree of change is required in customer behavior in order to earn a solid return on that investment? What is the statistical delta between present customer behavior and enhanced behavior that will make a difference to the profitability and efficiency of the entire enterprise? How is customer profitability defined within the enterprise? Based on the product or service sold, does the company have a high or low transaction frequency with its customers? What are the operating margins of the business? Does the organization understand what the lifetime value is of its various customer segments?

Without an intimate understanding of the customer profitability dynamics of your organization, the best intentions of a loyalty initiative will likely yield little long-term benefit. Ask the hard and uncomfortable questions up front. Be absolutely certain there is a thorough understanding of the profit dynamics prior to designing a loyalty program.

There is an old adage that the customer is always right—but this is very dated marketing theology that does not typically lead to effective loyalty management. In fact, companies with a detailed understanding of which customers contribute the preponderance of revenue and profit do not spend their resources equally on all customers.

In the 21st century, the term caveat emptor (buyer beware) has been replaced by caveat mercator—merchant beware! While this may seem counterintuitive to some, it highlights how one needs to understand the intricacies of the customer profitability dynamics to develop a successful loyalty program and set it on a firm economic foundation so that it can work for you for years to come.

Features and Benefits

How do the features and benefits of the program stack up against other loyalty programs in the general marketplace and within your specific market category?

With so many programs offered today and only so much appetite to carry numerous cards and keep track of multiple programs—consumers shop not only for goods and services but also for which loyalty programs they will actively participate in. Meeting or exceeding benefits offered by competitors' programs is sometimes not enough. Some loyalty programs that appear to reside within a completely different category (such as airline frequent flyer programs) in the eyes of the customer may still be competing with yours and affect the ability to attract and retain customers in your program.

Consumers have become very savvy in assessing a loyalty program, and whether they will participate. Though consumers may not even realize they do so, they quickly go through a checklist of questions about a program. If the answers to these questions are favorable, they will likely participate. If the answers are not favorable, they will not participate, regardless of how well the program is promoted. Some of these decision influencers are...

- Who is the sponsor of the program and how frequently the consumer already buys from the company? From the company's perspective, it hopes its loyalty program will promote new and more beneficial consumer behavior. Consumers try to determine how little they have to change their behavior in order to benefit from the program. Balancing the economic reality of the company goals with the desires of the customers can be challenging. What rewards does the program offer and what is the likelihood of the customers' earning them in the reasonably near future based on their present purchase patterns?

- What is the possibility of the company launching a program and then discontinuing it, prior to the customer receiving the reward? This is particularly relevant in programs where consumers will earn reward value that will build and vest over long periods of time—maybe even years. Programs such as these are the frequent-flyer, automobile, and coalition programs that offer a large reward in return for years of loyalty. Immediately after a major airline I often fly filed chapter 11, I received a mailing from the chairman of the company. He wrote to assure me that my frequent flyer miles were secure and to promise that the frequent flyer program would not be altered in any way. The airline did this because it knows how important the program is to the airline and it does not want to lose its best customers' patronage and loyalty that took years to build.

- Most importantly, consumers assess whether the company's product, service and how it performs to meet their needs is something they want to experience over time—regardless of how well the loyalty program is packaged and promoted and how enticing the rewards are. This further underscores the importance of executing consistently on the six Ps, as they serve as your first line of defense against competitors and will likely be your most potent and sustainable customer loyalty advantage—whether or not you ever launch a loyalty program of your own.

Reward Methodology

There are many different ways to reward your customers and provide value-added services. The ways that your program does this should be a logical outflow of the program strategy, coupled with the economic realities of your business. There are two divergent directions as it pertains to rewards and benefits, but they need not be mutually exclusive:

- Giving away "hard" benefits such as monetary rebates, or points good for tangible rewards, can be very powerful, but also very expensive. Some categories have favorable frequency and/or operating margins that support such an approach. These are called hard benefits because there is an identifiable out-of-pocket cost to the sponsor to provide these incentives.

- Other companies may lean toward "soft" benefits that tend to be more relational in nature. Special service lines and service numbers, member-only perks, various levels of recognition based on longevity and/or spending. These are all examples of soft benefits that cost the sponsoring companies little or nothing, but can further your loyalty objectives.

Based on market experience and empirical feedback from consumers, some of the most successful programs are the ones that effectively provide a balance of hard benefits that appeal to consumers' "left brain," or rational thinking, and the soft benefits that are more emotive and "right brain" in nature. Weaving hard and soft benefits within a program provides consumers multiple reasons to engage in your program and increases your chances of migrating transaction-oriented customers into highly loyal advocates.

Many consumers considering to enroll in a program will actively seek to "understand the math" in an effort to determine what the value of a point, mile, or reward is. Some customers simply want to understand the value of the reward they will earn in return for their patronage, while others are actively seeking to "game" the program. Though this should be expected and cannot be avoided, companies need to understand that consumers will likely "crack the code." Accordingly, the loyalty program and its rewards and benefit structure must be able to hold up under such scrutiny.

Metrics and Measurement

You are what you measure. To ensure you are measuring the right metrics, look back at your program strategy, what it is seeking to achieve, and what key measurements are central to achieving it.

One thing is central to most every successful loyalty program. They are all trying—one way or another—to entice more customers to buy more products and services, more often, over a longer period of time. In selecting the metrics that will be tracked and measured, it is important to ensure that these metrics will enable you to reasonably prove causality between positive changes in customer behavior and the loyalty program. While it is harder for some companies to do this than others, it is imperative that adequate program performance information (as deemed by management) is readily available in order continue to receive the ongoing support and resources necessary to sustain it.

What types of customer behavior will be accretive in terms of incremental profit, whether frequency of purchase, share of wallet, share of household, propensity of repeat purchase, etc.? One needs to determine the hot buttons that most affect profitability within an enterprise and are leading indicators for increased spending and frequency in the future.

Voice of the Customer

Regardless of how successful an organization manages the six Ps and a loyalty program, some customers will still stop buying your product or service.

As unpleasant as the task can be, organizations must obtain honest answers to straightforward questions about customer defection. Have customers stopped buying because they have found a better alternative or a similar one at a better price? Is your customer service part of the solution or part of the problem? Have some of your customers simply stopped buying products and services in the category altogether?

Answers to these questions serve as the backbone of an ongoing research and market intelligence feedback loop that should be part of any well-constructed loyalty program. Insights gleaned from this feedback should be used to actively update and refine the way the company engages and serves its customers, both in the loyalty program and throughout the six Ps.

The Impact of Loyalty

The two nagging questions for many companies is (1) does loyalty really matter, and (2) do loyalty programs positively affect the ability of companies to initiate and nurture longer and more profitable relationships with customers?

The answer to the first question is "absolutely yes." Over the past decade, numerous studies have helped companies understand the dramatic opportunity costs of not managing loyalty effectively—or, stated more positively, the tremendous financial leverage provided by achieving incremental loyalty. One study proved conclusively that companies that can improve the retention of their best customers by as little as 5% can increase enterprise profitability by as much as 75%.

There is no pat answer to the second question—whether all loyalty programs actually contribute to building loyalty. That's because different companies have different programs and may experience very different results. Also, it's sometimes hard to determine from the outside looking in as key performance data derived from these programs is highly proprietary and, as a result, is hard to come by.

It is probably fair to say that there are examples of highly successful programs, some dismal failures, and many that fall somewhere in between.

However, companies that manage their six Ps effectively and then add a well-designed and well-executed loyalty capability are in the best position possible, as the program can accentuate and reinforce an already high-performing value proposition.

Loyalty programs will never take the place of doing the basics right, but they serve an important role for many successful companies and add significant economic value to their enterprise.