At a time when the old broadcast model is collapsing and familiar advertising nostrums are being debunked daily, marketing is in a panic to restore its dwindling credibility as a discipline.

There is pressure as never before to show something for the dollars being spent. Corporate bosses everywhere are insisting on it. Media choices that used to be routine are suddenly being questioned. Budget allocations that were once automatic now have to be rationalized. Marketers keep hearing the pushback: "How do you support that?"

The ethereal benefits of brand building are no longer enough to win over tough-minded CFOs—not when the link to top-line revenue growth is still more theory than fact. And so marketers are anxious to find tangible evidence of their contribution to business performance. The search is on for more meaningful metrics: numbers everyone can relate to—and believe in.

That's why marketers can be heard mimicking the language of accountants, seeding their vernacular with terms like return on marketing investment (ROMI), discounted cash flow, and hurdle rates. Yet no one has truly cracked the code on ROMI. It remains a quixotic pursuit, with no clear way to correlate marketing spending with financial results.

No matter how illusory it may be, the quest for an integrated performance measurement system—one that conclusively establishes the value of marketing—is a priority for many businesses. According to Forrester Research, measurement has become a "battle cry across the marketing industry"; it also tops the list of complicated tasks.

A recent survey jointly conducted by Forrester and the Association of National Advertisers (January 2005) found that 80% of respondents could not even agree on a common definition of marketing ROI, let alone a method of computing it. And because ROI is expressed as a ratio, there is a hidden risk that goes with it: the measure looks just as good when the cost denominator is reduced.

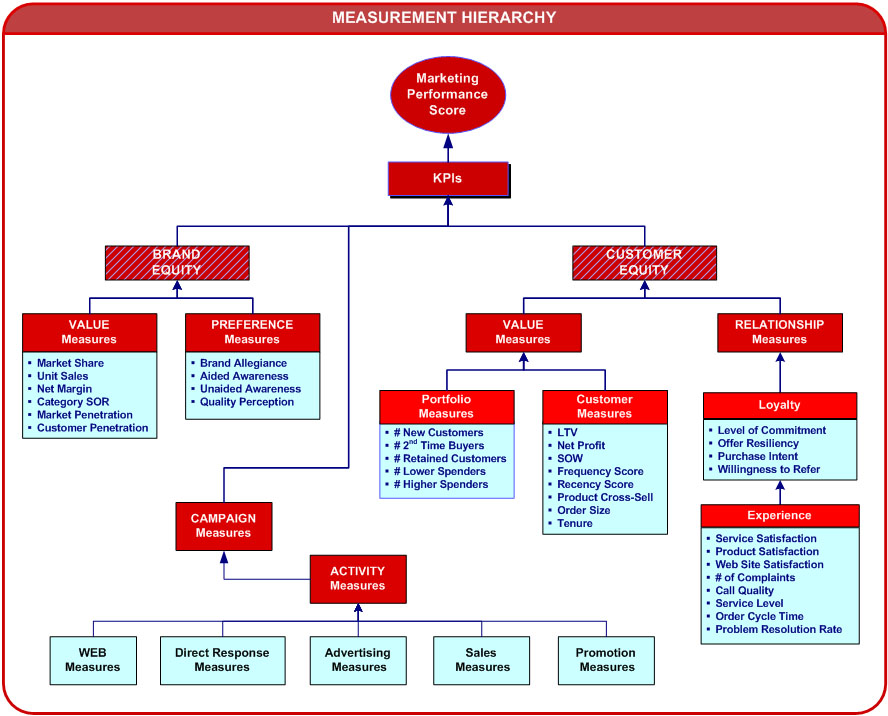

In his book Marketing ROI (McGraw Hill, 2003), James Lenskold states that "without question, smarter marketing can generate more profitable returns, so it's time to manage the budget as an investment and not as an expense." He adds: "The key to using marketing measurements effectively is to understand how the measurements relate to one another."

Line of Sight

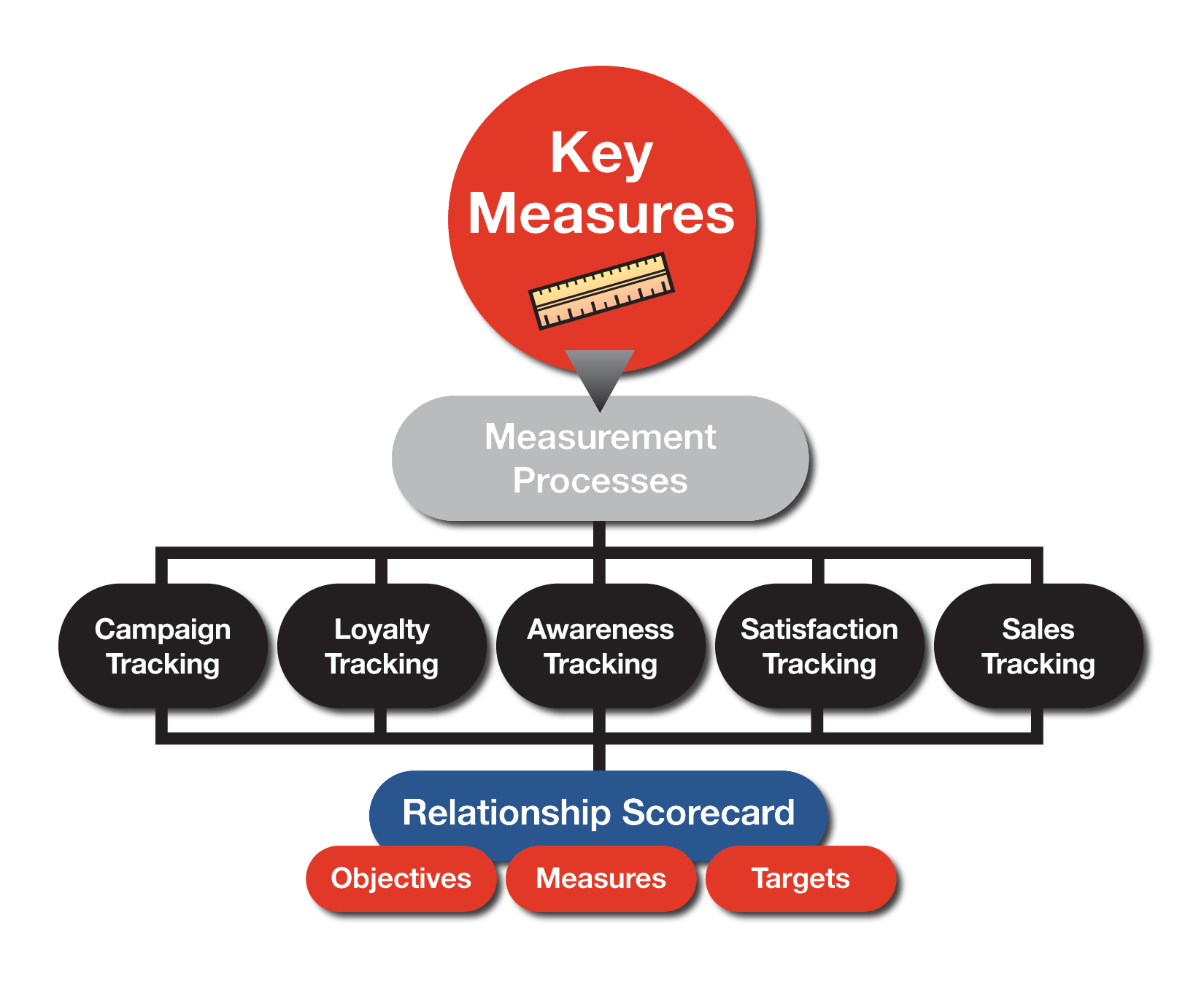

In the past, all marketing management ever really cared about was driving up market share and sales orders—because that is how they were judged from one quarter to another. Brand nurturing companies might also pay heed to intermediary measures such as top of mind awareness and purchase intent, seeing them as lead indicators. But until recently, much of what has passed for marketing measurement has been street-level reporting: gross ratings points, coupon redemptions, Web site visits, direct mail responses, trade show leads, and the like.

No marketer can hope to show that any one tactic is more financially advantageous than another. How, after all, does anyone prove the merits of in-store signage over outdoor advertising? Collateral support versus event sponsorship? Product sampling versus promotional contests? Those decisions always get made through a subjective mix of instinct, professional bias, guesswork, industry practice, agency prodding and, oh yes, past resul—if they can even be obtained.

The real question is whether the cumulative marketing investment is paying off. Just as important is figuring out the most appropriate balance between the acquisition of new customers and the retention of existing ones. Too often, the allure of mass advertising has deprived the best customers of the attention and stroking they deserve. But with the deconstruction of mass media, the rapid rise of interactive marketing, and the realization that the customer experience matters, CRM is in vogue again. The result: an even greater diffusion of media spending, making the measurement labyrinth that much more complex.

Some leading marketing organizations, particularly in the consumer packaged goods sector, think that the solution lies in market mix modeling. According to Forrester, it has become the preferred measurement technique, with more than 40% of marketers planning to adopt it in future.

First introduced in the 1980s, market mix modeling uses time-series regression to weight the various activities that drive sales, such as advertising campaigns and in-store promotions, and then predicts the impact of using various combinations of media. The model is reliant on a rich source of historical data spanning 2-3 years (usually drawn from POS systems). The drawback to this method is an undue emphasis on short-term results, which gives promotional tactics an undeserved edge over investments with a longer payback (such as loyalty building). Anything that causes a sharp spike in sales is interpreted as a win. Yet that revenue may not be sustainable—in fact, it may undermine the brand franchise by encouraging excessive discounting.

An alternative approach, favored by CRM practitioners, is to model customer value instead of brand sales. In their forthcoming book Return on Customer, Don Peppers and Martha Rogers observe that "a company is, at its roots, a portfolio of customers, who not only buy things from the firm in the current period, but also go up and down in value." Therefore, the most important indicator of business health, they posit, is the current period cash flow from customers plus projected changes in their equity (i.e., lifetime value).