This article is simply about complexity. It's not about the usual product complexity often discussed in marketing journals, business magazines or even in the pages of the New York Times. Instead, I am speaking of a "new complexity" that has recently permeated high-technology consumer products and services to create products with massive features sets and corresponding levels of operational complexity. This new complexity will fundamentally alter the role of marketing and product development executives and redefine the skill sets necessary for achieving business success in the future.

A simple structure for a complex issue: This article is divided into four sections. Section 1 defines in detail the rationale and supporting research for this new and important form of product complexity. This first section explores broad trends and makes specific references to emerging product categories that reflect this new problem. Section 2 presents a detailed case study based on research from MP3 internet-based music systems. The case is drawn from an in-depth examination of the Apple Computer on-line music customer experience and that of related competitors. Section 3 defines the implications that this new complexity has for marketing and product development executives. In Section 4 the article concludes with an assessment of usability science followed by 10 management principles critical to achieving success when dealing with the new complexity problem.

Section 1: Trends in Product Complexity

How big is the problem? The actual scope of the complexity problem is rather startling. For example, in most high technology products and services, customers do not use more than 10-12 percent of the total feature set being delivered to marketplace. These percentages hold true for everything from PC software to PDAs. With each new generation of high technology consumer products, including cell phones, MP3 players, digital cameras, even televisions, manufacturers increase their feature sets by approximately 28 percent1.

However, the embedded feature set of new products is a small percentage of increasing feature density and associated interactive complexity. By adding new levels of connectivity to these already complex products, customers have access to vast new feature sets which are not directly resident in the software or hardware of the products themselves. This is called "feature density transparency" and is a fundamental component of the new complexity.

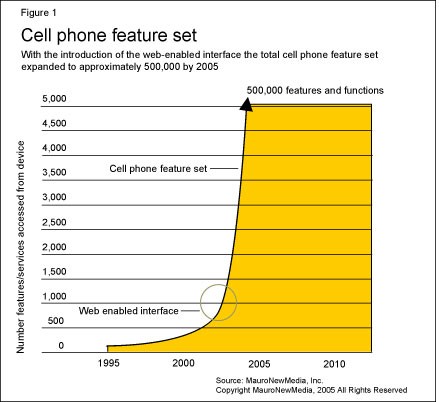

The migration of features and functions: For example, as Web-enabled interfaces become integrated into products, the total feature set expands beyond comprehension. In 1995 the total feature set2 for cell phones offered customers about 50 different embedded functions. Today, cell phones are capable of accessing an estimated 500,000 features and functions through the combination of embedded functions and web-based interactive services.

Figure 1 illustrates that the complexity of cell phones has increased at a staggering rate over the past five years. Make special note that Figure 1 is actually cropped on the upper range. A complete visualization of the data would extend vertically several pages. The critical point is that feature density is accelerating as products become smaller, more interactive, and hyper-connected. These three variables are combining to create truly staggering new levels of operational complexity.

The conventional marketing view of complexity: The "complexity problem" is known by marketing executives to be a double-edge sword since the addition of features and functions provides a familiar conceptual framework for new marketing campaigns which focus on increased functionality at lower cost per feature. In fact, there are those in market research who say that increasing feature density in products is actually a core reason why consumers purchase new products and services or upgrade what they already have.

The "paradox of enhancement" problem: Robert J. Meyer and Shenghui Zhao, professors at Wharton School of Business, and Jin Han of Singapore Management University have recently published a study3 showing that consumers often make purchase decisions based on the concept that they can and will make use of an expanding feature set. However, Professor Meyer and colleagues go on to show that these same consumers actually end up ignoring new features and returning to basic function after a relatively short experience period.

This problem, which the authors call the "paradox of enhancement," is one of the dirty little secrets of both corporate product development and marketing groups. Marketing executives tend to believe the formula "more features = more customer benefits" will retain salience in the future. Unfortunately, the party may be over sooner than we think. Products are fundamentally evolving in ways that will have profound impact on how traditional marketing views feature density and interactive product complexity.

The "products are becoming processes" trend: For the first time, many new high technology products are no longer stand-alone entities, which can be optimized and marketed within a narrow band of expected customer experiences. Now, many of these products have become component parts of a larger and more complex matrix of customer experience touch points. These include: Web sites, desktop applications, home media centers, customer support systems, retail demonstration platforms, and peer-based information transfer options, such as blogs, informal/formal on-line product reviews.

This new flow from "products-to-processes" is a byproduct of ubiquitous communications protocols such as TCP/IP and related Internet infrastructure, combined with the momentum of Moore's Law4. When compared to prior generations of consumer technology, these news products and services are "hyper-connected." This recent migration from "product to process," brought about by hyper-connectedness combined with increasing feature density, is at the core of "the new complexity problem." These factors will have a profound impact on the customers' interactive experience.

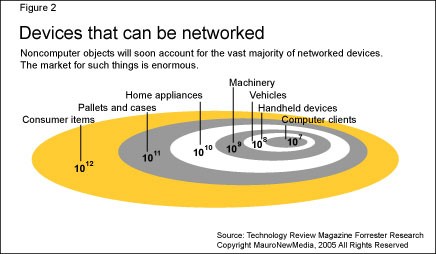

The massive new connectedness: As can be seen in Figure 2, the total number of devices that can be networked is expanding at a staggering rate. However, the more interesting point revealed in Figure 2 is computer clients5 will account for the smallest total number of future networked devices. In Figure 2, the largest number of devices will reside in the consumer products category.

Clearly, an objective of future software and hardware development will be the realization of the "ubiquitous"6 computer. However, these new hyper-connected consumer products will introduce all manner of interfaces requiring customer intervention. There is a tendency on the part of technologists to think of this new level of complexity as a technology problem where new interface concepts or automation will solve the problem.

Is automation the answer? Thinking that new interactive modalities like voice-activated interfaces or even higher levels of automation will dramatically reduce interactive complexity is naive. With the onset of hyper-connectedness come billions of new customer experience touch points. It is no stretch to see that these same issues will have a major impact on how products are designed and engineered.

In the design of advanced man-machine systems, the use of automation is known to be so complex that these problems are addressed by a sub-specialty of "usability science"7 known technically as "function allocation" research. Effective use of automation is in reality a complex cognitive science question which, if not properly understood and modeled, creates products that are neither empowering nor easy to use. This problem is known as the "paradox of automation" and can only be dealt with effectively through the application of function allocation research.

The cognitive science behind the new complexity problem: in raw information processing terms, this new complexity is determined by the sheer number of cognitive units that the customer is forced to deal with in the process of executing all manner of tasks and decision making routines. However, in psychological terms, this metric is known to be a crude measure that reveals only the extent of the problem but not its true cognitive structure.

When employing more robust forms of cognitive science, such as cognitive task analysis; key stroke level modeling; transfer effects analysis; or skill acquisition theory, it becomes clear that consumers are facing complexity at a point of inflection. The process of combining these new methods and research from allied fields is resulting in a new discipline known formally as "Usability Science." When applied rigorously, this new science helps define and solve critical aspects of the new complexity problem.

In cognitive terms, it is well known that for every new cognitive unit that is added to a task, the time to complete the task increases, as do errors and skill acquisition time. More cognitive units means simply more decisions on the part of the customer.

A widely accepted theory of cognitive complexity, known as "Hick's Law,"8 allows us to formulate a way to measure this change and quantify the jump from one cognitive unit to many. Because the time to make a decision increases at a startling rate with an increase in the number of complex choices, it can be shown that the new complexity is causing customers to spend far more time interacting with products and services. In some examples this time includes access to and use of basic functions.

From other cognitive science principles, it can be shown that both errors and learning time also expand at a startling rate as complexity increases. Clearly customers can learn to use some features and functions of these new products and services, but the level of cognitive workload required to obtain proficiency is expanding beyond objective, functional benefit in many products.

What about subjective performance? Hicks Law says nothing about the subjective aspects of using products and services such as joy, empowerment and satisfaction. Additional methods from cognitive science tell us a great deal about these other key attributes and what they say is not promising. The new complexity can lead to products and services that are not only more difficult to learn and use but less satisfying and empowering. All of this is a rather scientific way of saying there is sound cognitive science behind the new complexity problem. Looking at the science of complexity shows that we have reached a critical point where solving the complexity problem will be a central theme of successful products and services in the future.

Section 2: A Compelling Business Case

Here's a model of the new complexity: By examining MP3 players, it becomes clear that these highly popular products are now simply an element of a much larger marketing problem. In fact, what these products are really all about is internet-based music and related information delivery. MP3 players are a node on an rapidly expanding network of other systems and customer interfaces which include: music desktop applications; PC desktop interfaces; Web sites; augmentation products; on-line payment services; subscription services; and existing hard copy versions of CDs. Recently, one can witness the predictions of network science as MP3 players are now interfaces to a wide range of additional content forms, including: podcasts, radio, photo, video, and GPS related data sets. Objectively, how large is this matrix and what types of products will inhabit this new information space?

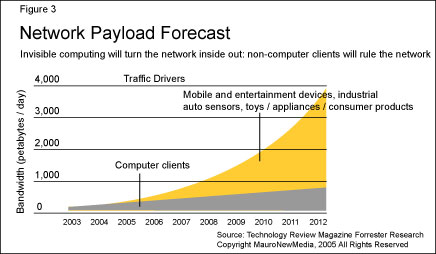

Network payload and consumer products: The trend toward hyper-connectedness is in an early phase. In data published by Technology Review, the magazine of MIT, the true extent of the "product to processes" flow is revealed. In Figure 3, one can see that in the coming years, devices other than computer clients will consume the vast amount of network bandwidth. This data further supports the point that network demand will be driven by everyday products and services, not computer clients as was predicted less than 10 years ago. Internet-based music products and services are a powerful reference point for this new trend.

It becomes clear that the success of an MP3 player is actually tightly bound to the overall performance of the component parts of the Internet-based music business model. What marketing executives traditionally saw as a "product marketing problem" actually becomes a "process marketing problem." This adds a new dimension to marketing programs as both methods and best practices do not adequately reflect this shift in focus. As will be discussed in Section 3, the implications are "large" as the marketing problem now becomes one of understanding and marketing an "entire customer experience."

Customer experience optimization is not a new idea. The concept of customer experience optimization has circulated in the marketing literature for 20 years or more. In a 1994 article for Marketing Management, author Louis P. Carbone put forward the basic concepts of customer experience design, including the need to optimize the entire customer interaction value chain. More recently, the concept of total customer experience optimization has become a central theme in leading business books, including Good To Great, by Jim Collins.

These books uniformly make the case for customer experience optimization but do not reveal either the structure or complexity of the task. Therefore, marketing executives are left without a model for making critical marketing and product development decisions related to optimization of the total customer experience. This is no surprise since traditional market research methods were not created to address the optimization of the total customer experience.

Existing market research does not reveal the problem: When one employs traditional market research methods, such as group focus, segmentation analysis, or even simple usability studies, the structure of the new complexity problem is not revealed. However, by utilizing more advanced levels of "usability science" to evaluate the entire customer experience, it becomes clear that for the first time consumers are facing interactive experiences where core functions cannot be fully utilized, not to mention advanced features.

In leading consumer electronics companies, this message has not penetrated product development methods in a meaningful way. This view is supported by business cases that reveal the nature and extent of the new complexity problem. World-class corporations like Sony (and others) have lost major market share in some product categories due in large part to their inability to detect and deal with the new complexity problem.

Theory and practice in product development: In a recent study9 from the consumer electronics sector, which focused on benchmarking internal market research and product development methods, it was shown that a series of world-class corporations simply did not understand how complex their products have become or the impact the new complexity was having on critical customer purchase decisions and use behaviors.

The more surprising insight from this analysis was that many of these corporations had in place large teams responsible for the design of the "customer experience," yet their newest products and services were reaching customers with usability and customer experience design problems that were extensive and damaging to their brands. It seems that even those charged with simplicity cannot deal objectively with the new complexity.

The current discrepancy in customer-centric development methods: From a public relations perspective, many of these corporations maintained highly articulated product development and marketing process models under an array of acronyms. However, they uniformly lacked an operational understanding of formal usability science and how to use this new science to design and test the entire customer experience. Several of these companies made frequent industry presentations on the "customer-centric" nature of their product development and marketing methods, even though usability science showed their products to be essentially unusable by critical customer profiles.

The silo effect: In many corporations this problem is especially pervasive as critical customer experience segments are created and managed in a silo-based management model that insures various divisions charged with creating solutions do not work together to achieve an optimized total customer experience.

Recent studies10 that focused on examining the total customer experience for several high technology products found that primary customer experience segments were either poorly aligned or simply in conflict. The net effect was increased operational complexity for the customer. As products migrated to higher levels of connectedness, the problems became more frequent and damaging to the customers total interactive experience.

CDs vs. MP3s: In studies that focused on Internet-based music services, poorly functioning customer experience segments were common. In several systems, the customers' overall interactive flow was so impoverished that they were forced into a "random walk"11 of the product interface in an attempt to complete the process. Throughout the total customer experience, it was found that retail store presentations were confusing; package designs presented inaccurate system requirements; products were too complex to be usable; instructions were confusing and missing critical information; desktop applications would not communicate with hand held players; music web sites were so difficult to understand that respondents simply gave up after attempting purchase of songs.

These problems became especially prominent in complex business models like Internet-based music subscription services. Successful completion of the entire initial set up and first time use of the basic customer interaction sequence required an average of four hours, with customers encountering an average of three termination events which required call-center support or expert intervention.

Compare this to set up and first time use of a traditional CD Walkman, which requires on average 5.5 minutes once the blister pack is opened. When one understands the extent of the new complexity problem, it is no surprise why Professor Meyer and colleagues found their test subjects returning to core features. This puts the "paradox of enhancement" in a new light which may have more to do with cognitive workload and skill acquisition than with underlying consumer purchase behaviors. Where are the success stories in this new complexity?

Current "Best-In-Class" is still not an "A" student: It is clear that Apple Computer has understood the concept of "products becoming processes." The Apple Internet-based music system, comprised of the Apple retail setting, package design, iPod players, iTunes desktop application, and Apple Music Store, is a frequently cited example of successful "customer experience optimization." Apple's ability to deal effectively with the entire customer experience is the essential reason for Apple's success in the internet-based music space. Clearly Apple has created high value solutions in most interaction segments... but not all segments.

Where was that function? For example, the Apple iTunes desktop application is complex and confusing for some critical user profiles. The detailed reasons for this are explained by usability science. However, on a basic level, the highly simplified "look and feel" that Apple strives for in the design of the iTunes interface is achieved by elimination of button labels and supporting graphics. This has a significant negative impact on inexperienced users and those who interact with the application infrequently.

Other problems with the Apple iPod customer experience are revealed by formal usability science, including segments that would have presented a serious problem had Apple not employed automation as a means of smoothing the customer's experience through the process. Apple's use of automation in iTunes solved some of the complexity problem, but added complexity back into the customer experience for more experienced users.

Smoothing the initial customer experience for some users: For example, in the Apple iTunes/iPod interface, automation takes over the first time customers attempt to transfer music to their iPod from iTunes. At this point in the customer's total interaction sequence, Apple makes use of automation to ensure that the first attempt to transfer songs between desktop and device is successful.

This is not a trivial decision, as this actual task segment is known in usability science as a "critical incident." Understanding which customer experience segments are critical in achieving high levels of initial satisfaction is a complex issue requiring research methods not associated with routine product testing or market research. From a strategic marketing point of view, this was an important decision for optimizing the initial Apple customer experience.

However, Apple's use of automation to solve a problem for some users of the process makes it complex to selectively manage which songs to move from iTunes to the iPod. If you want to regain a measure of control over the transfer process, iTunes again becomes complex.

For customers with advanced skills and motivation, this is not a problem. However, for those with less technology awareness or motivation, the process begins to breakdown. In fact, studies show that most consumers simply set up their iTunes so that all content saved in iTunes transfers each time they connect their iPod. Again, this is an interesting and useful example of the "paradox of enhancement." Even though significant problems exist with the Apple internet-based music customer experience design, no other entrant in the internet-based music space has done nearly as well.

Why the iPod is easy to use and why it is important: Formal usability science explains in objective terms why an iPod is far easier to use than a major competitive brand. But ease of use is only one dimension of the iPod success formula. Not only is the iPod easier to "use," it is much easier to "learn." This is an important distinction for marketing executives. When one structures a professional usability study of MP3 players, this new science reveals startling insights.

For example, when a new customer is given an iPod for the first time, they require about 60 seconds to develop a workable understanding of how the device functions (assuming it is turned on for them). On the other hand, when a new player from a major competitor is given to customers for the first time, they may work with the device for up to 10 minutes and still not accurately capture an understanding of basic functions. Why is this important to the marketing of new products and services?

Who really sells these new complex products? Increasingly, purchase decisions for complex high technology products are being formed by peer recommendations and peer acceptance. This is especially true for life-style products like MP3 players, as price seems be a less salient purchase decision variable. Peer recommendation is dramatically affected by how quickly customers learn to use and demonstrate features and functions to their friends and family. It is almost impossible to conduct a usability science study of MP3 players without accepting the fact that respondents have somehow been shown an iPod by a friend, even if they do not actually own any MP3 player themselves. This whole idea of the demonstration performance of a new product is completely wound up in how complex a product is to learn. iPod is a relevant example of how "skill acquisition theory" can be used to explain why products are easy to learn. This same skill set can be used to design new products that have these same attributes.

A new definition of "life-style" positioning: Apple's commitment to total customer experience performance is revealed in the marketing of the Apple internet-based music system, which places virtually no focus on features or functions but positions the overall customer experience as the Apple value proposition. The most relevant point is that Apple actually delivers on its value proposition for most critical customer touch points. Apple has carefully thought out the upstream and downstream implications of each key segment. This view creates a new definition of "life-style" positioning where the focus is more correctly on "life-cycle" performance, resulting in improved "life-style" positioning.

A narrowing of focus as the customer experience broadens: While it may seem that the Apple iPod customer experience is the end game in internet-based music systems, nothing is so clear in these complex networks of products and services. There is ample opportunity for others to enter this space with products that are both easier to use and more empowering than the Apple system.

Paul Thurman, a Professor at Columbia University states, "The range for making the wrong product development or marketing decisions has narrowed significantly. One decision variable is clear: any product that migrates away from robust usability, without taking into account the end-to-end process, will create below-average returns for their makers and marketers. Sony's brief attempt at setting a new digital music format standard—ATRACS—and then building an entire network of products, Web-based software, and experiences around it is a good example."

As the recent quarterly profits at Sony attest, these decisions were devastating. Clearly, in the near term, Sony has abdicated the portable music device market to new entrants. In the new world where products are migrating to processes, communications flow is the glue that binds these new business models. A corporation that believes it can create a technology platform or format that in any way restricts the smoothness of the total customer experience is heading into "terminal complexity."

Section 3: The New Marketing Complexity

When the whole is truly greater than the sum of the parts. There are important insights for marketing executives flowing from the Apple success story.

For example, by combining usability science and econometric modeling, it is possible to develop an accurate picture of how performance in each customer experience segment impacts the overall business model. When one customer experience segment of the total value chain drops or fails, the entire process fails. From the application of usability science, we know which segments fail and in exactly what way. In usability science, the concept of "errors" has a formal definition. When systems force users to make errors, the way in which such errors are detected and corrected determine to a great extent the usability of these complex new products and services.

Applying metrics to errors allows development and marketing teams to model such events in economic terms. These models map directly to the success of longer term marketing objectives and brand building. It is no surprise that this data is useful in determining the overall business impact of such problems.

Cognitive segmentation: The "new complexity" casts a bright light on traditional segmentation analysis, which factors customers by relevant demographic and purchase decision variables but fails to define the customers' actual cognitive performance, including their ability to learn and to use these new complex products and services. Take, for example, the development of customer profiles, a critical component of all successful product development and related marketing programs.

The Least Competent User (or LCU) is the most important segment: In usability science, customers are segmented by cognitive profile, which includes experience and ability to deal with the new complexity. For a given product or service, customers undergo "cognitive segmentation" of their skill acquisition, transfer of learning profiles, and technology adoption variables. Based on these criteria and others, customers are organized into three basic profiles according to ability to learn and use high technology products and services. These profiles are: 1) LCU: least competent user, 2) ACU: average competent user, 3) MCU: most competent user. When this new model of customer behavior is mapped onto traditional segmentation research, several important insights result.

For example, in MP3 players, the vast majority of those who will purchase MP3 players over the next 2 to 3 years (some 22 million) fall into the category of LCU. These are exactly the customers who will find usability and empowerment a core factor in purchase decisions. Clearly the lion's share of the market goes to those manufacturers that design for the LCU, not the MCU.

The LCU cognitive segmentation ranges across all traditional segmentation profiles to form a more robust view of the critical product development decisions that must be made to create products that will appeal to the absolute largest customer base. Traditional segmentation research tells you who may purchase the product but it tells you nothing about how to create a product that appeals most directly to all profiles.

What can be controlled: Compared to the competition, Apple Computer had an easier time developing an optimized total customer experience. This is due in large part to Apple's ability to control most of the customer experience interaction chain, starting with the Apple retail setting and ending with the on-line Apple Music Store. However, having control of the entire customer experience is no guarantee of success, as others had this same opportunity and failed spectacularly.

Realistically, most corporations will not be able to effectively control the entire customer experience interaction sequence. This further complicates the role of the marketing executive. For instance, if you produce MP3 players as a stand-alone product category, you must contend with the larger issue of customer experience segments that you cannot control. This places new demands on the marketing team. Take the following example, again from MP3 players.

Be careful what you wish for: Let's say that you negotiate a promotional deal with Yahoo Music as part of your marketing plan. This allows you to have your player promoted on the Yahoo Music home page. But a series of underlying issues that you have no control over, can and do intervene to impact the success of your marketing plan. Specifically, you may not have reliable and objective data on the usability of the Yahoo Music customer experience.

In fact, the Yahoo Music customer experience segments, which your device must interface with, may be optimized for Yahoo Music and not your player. It is critical to understand that those who control your upstream and downstream customer experience segments may not have the same objectives or business practices as your company. They may in fact be your direct competitors.

How your business partners can damage your value proposition: Try and find a clear definition of the underlying business requirements of the current online music subscription services. Customers must search deep into the text of disclaimers and installation procedures to understand exactly why they suddenly cannot listen to the content on their new MP3 players. Hidden in the details of the customer agreement are critical customer experience rules that dictate how a subscription service is going to allow them to use subscription content.

This makes consumers angry on a whole new level that spreads across the entire customer experience value chain. Even if your new MP3 player is brilliantly designed, encouraging your customer to link to a discount subscription service that holds their music hostage for no apparent reason is not going to help your value proposition.

Upgrades can kill the best customer experience: Again, taken from the Yahoo Music example, there is a second tier of complexity problems that impact the success of your marketing efforts. This problem is known in usability science as the "firmware upgrade failure." You have no control over the fact that the Yahoo Music player (desktop application) will be upgraded on a frequent basis, which means that even though your player may be marketed on the home page of Yahoo Music, it may suddenly require a firmware upgrade to work with the latest Yahoo Music desktop player. This process can happen while your player is being promoted on Yahoo Music. Once customers detect that a firmware upgrade is required, the sale of your player may drop like a stone, yet you remain committed to pay for the space on Yahoo Music.

What this means simply, is these new products and services can present customers with levels of complexity that cannot be controlled across the entire customer experience value chain. This is a major business issue for corporations plying this new space.

New customer experience segments: To expand on this point, once a device requires a firmware upgrade, marketing's role expands to include the customer's experience related to the firmware upgrade task segment. This includes: design of the landing page on the site where customers will deal with the upgrade and the design of call center scripts for use when support calls spike due to the firmware upgrade issue.

Research indicates that most consumers have minimal understanding of what a "firmware upgrade" is all about. Therefore, plan for extended call times as your support center takes customers through complex debugging tasks requiring interaction with: your MP3 player; the customers' other desktop applications; their operating system interface; and the Yahoo Music player.

Clearly this new trend of products becoming processes dramatically complicates and expands the problem space of marketing professionals. The previous "firmware upgrade" example drawn from "post-purchase" customer experience segments makes the assumption that customers have actually purchased your product. This is not a foregone conclusion as the customers' "pre-sale" purchase decision dynamics are also being dramatically altered by the new product complexity.

How new retail models flow from the new complexity: Conducting a formal usability science test of products and services can be used to improve the success of your marketing campaign well before it is launched. For example, by defining in objective terms the complexity of a product and mapping that data to purchase probability models, you can predict that, no matter how good your marketing campaign, you will never benefit from peer recommendation. You will also know before you spend a million dollars on in-store promotion that you may have a major problem.

For example, if your product can be handled in a retail setting next to competitors that are far easier to learn, the problem grows in a way that can be statistically modeled. Therefore it is better to negotiate a deal that keeps that competitor off the demo stand. Of course, this may not be possible as smart retailers observe this dynamic everyday. Aside from agreements to educate their employees on "preference sales" strategies, leading retailers are ultimately in the business of creating repeat customers based on optimizing "their" customers' total interactive experience.

In this rapidly changing retail environment, product complexity equals time, and time equals money. Clearly, these relationships can be modeled and simulated long before products reach the sales floor at Best Buy.

Smart retailers are rapidly getting the point that they have control over the purchase of complex high technology products and services simply by assisting consumers through the early customer experience segments. These same retailers realize that their "total customer experience" is what drives their revenue models. A customer who leaves Best Buy with an iPod is going to be a happier customer in spite of the fact that the Best Buy "Blue Shirts" may have been trained to demonstrate a competitive product. Taken from this point of view, one can see immediately the long-term strategy of the Apple retail store initiative. In this regard, Apple Computer is strategically mapping complexity resolution to the retail sales model.

The new marketing decision space: This puts yet another new perspective on the types of issues to be faced by those who market high technology products and services. In cases where the new complexity reigns, you are well behind the curve before the customer cuts open the blister pack. The concept of increasing product complexity and its impact on marketing creates a new level of problem for marketing executives.

Again, Paul Thurman, Professor at Columbia Business School, states: "What was previously thought to be a matter of creating a successful combination of the famous four Ps (Pricing, Promotion, Placement, and the Product feature set) now turns out to include the need to fully understand the actual complexity of the product or service and the impact it will have on customer purchase behavior." In a critical way, this additional complexity impacts on marketing decisions and basic product development planning.

The Empowerment Gap: The new complexity creates major problems for executives in marketing and product development. However, in a surprising way, it also offers new opportunity for those who employ usability science to create cognitively appropriate and empowering products and services.

For example, in a product category that is growing increasingly complex, a product that surfaces which is easy to use and empowering creates an immediate "empowerment gap." The iPod is an obvious example of this gap formation principle. There were literally dozens of MP3 players on the market before the iPod. All were complex and simply not empowering over the broader customer experience. Apple Computer created a substantial "empowerment gap" by combining the iPod player interface, a cognitively robust solution, with other acceptable but not outstanding customer experience touch points. However, the total experience is undeniably empowering.

There is tremendous intellectual and business capital in the "empowerment gap" model. These solutions can dominate vertical markets at a startling rate because they solve one of the major problems defined in the Paradox of Enhancement. Products and services that actually produce an empowerment gap create enough customer motivation to undergo "feature adoption," not "feature rejection."

In a recent study of the iPod interface it was shown that customers actually use on average 85 percent of the total feature set in the original iPod. These types of solutions are a fundamental win for those corporations that can deal creatively and objectively with the new complexity problem. Such solutions can be leveraged across a broad range of business problems.

Should Apple Computer generalize the "cognitive principle and interactive simplicity" of the iPod interface and apply those principles to other consumer electronic categories, they can be a major player in the overall CE space. This does not mean simply integrating a "click wheel" interface into other products but implies creating the same "empowerment gap" in other categories by leveraging what makes the iPod interface cognitively robust and empowering.

This is a big leap for Apple Computer and other major manufacturers as they may not have the development culture to create or make use of such generalizations in the broader business context.

Section 4: The Road Ahead Is... Well, Complex!

Journalists, as usability experts, are a major headache: In a recent article12 posted on Knowledge@Wharton, the author Professor Barbara Kahn discusses the impact that leading technology journalists have on consumer decision-making with respect to high technology products and services. In that piece, Professor Kahn states, "The Mossberg Factor matters a lot. He is no longer Everyman because he knows much more than most people about technology." The importance of this insight cannot be overstated.

Also, in a recent article13 by Kahn, it was found that leading journalists reflect user profiles that are a small subset of the actual customers who purchase and attempt to use high technology products and services. That article dissects a recent "Business Week On-line" review of Apple iTunes and presents an example of how journalists sometimes create product reviews that are highly misleading on issues of ease of use and interactive quality.

A new road for consumer products: Over the past 25 years, "usability science" has been utilized to solve truly vexing man-machine problems in the commercial sector. These problems included process control applications; cockpit automation; financial trading platforms; and hundreds of complex military systems that would have failed without this new science. Usability science will become a critical strategic asset for world-class consumer product manufacturers striving to capture market share and to build powerful interactive brands.

It is not a simple road: The views expressed in this article are based on more the 25 years as a leading consultant in usability science. Over that period, our firm has created solutions to the "complexity problem" that have saved clients billions of dollars and allowed some to capture and dominate their respective markets. In the process of executing many usability science programs, reliable patterns have emerged that are common and important. The most important insight is that when rigorously applied, usability science is fundamentally a new way of conceptualizing the design and marketing of products and services.

This new science is initially disruptive and costly. For example, in a recent chapter14 from the book, Cost-Justifying Usability, An update for the Internet Age (Second Edition) by Randolph Bias and Deborah Mayhew, the authors make clear that this new science requires patience and commitment from top management and all marketing and development executives responsible for critical decision making. The authors identify core attributes that corporations must have in place if usability science is to be adopted successfully.

Clearly the road to simplicity is complex. For those corporations who wish to reduce risk and increase the probability of success in an increasingly competitive world economy, the road from complexity to simplicity will be well-traveled. Marketing executives can have a significant impact on solving the new complexity problem by employing methods that accurately define the extent and structure of the complexity problem facing their customers and by aggressively aiding product development teams in the resolution of these business-critical problems.

The take away: This article has identified the new complexity problem and its roots. It has presented an extensive discussion of the on-line music business model in the context of the new complexity problem. It has also discussed the impact that the new complexity will have on critical marketing and product development decision-making. Now, it leaves you with the following 10 principles found to be helpful when thinking about and creating solutions to the "new complexity problem."

10 Principles for Managing the New Complexity

- Do not assume that your design and engineering divisions are by default going to produce easy-to-use and empowering products and services. In this difficult transition period before design and development fully understands how to solve the complexity problem, it is essential for marketing to demand objective research on the operational complexity of new products and services during design and development. Be forewarned; these requests will not be met with a happy response.

- It is essential that you develop a comprehensive model of the total customer experience for all core products and services and put in place methodologies that document all critical task segments through the use of reliable metrics on ease of use and empowerment. The time has come for total customer experience optimization.

- Do not overlook the opportunity made possible by understanding the impact that increasing complexity is having on your customers' decision-making profiles. Be especially aware of new entrants into any product category that reflect high levels of usability and satisfaction when compared to other offerings in the market. Such entrants can and will capture market share at a startling rate.

- Do not assume that because your company has dominated a major product category in the past, you can overlook the impact of both increasing complexity and the product to process flow. As new high technology products and services reach the market in shorter development cycles, the "time to fail" is exceedingly short. You can migrate from market leader to single digit market share within 2 development cycles.

- When looking at your overall customer experience profile and interaction segments for new products and services, pay special attention to those segments which you do NOT control. Make it your responsibility to undertake a detailed examination of the usability performance and business objectives of your partnerships.

- Do not assume that because you have a department charged with design of the "customer experience," your products have solved the new complexity problem. Objective independent research is the only effective test of customer experience performance. Even those who may be charged with creating simplicity do not fully understand the new complexity.

- If you can create a product that delivers a measurable "empowerment gap," make full use of all intellectual property rights. These solutions can form the structure for dominating an entire product category. This is the so called "iPod effect." Create patent filings for these innovations that are based on sound usability science which documents user performance and related improvements and innovations.

- When you employ complex and expensive segmentation research, consider other important customer attributes that will help you understand the relationship between the new complexity and market share. These are not simple issues but will be critical when making longer-term strategic decisions.

- To the greatest extent possible, create a balanced and fully supported response to journalists who publish reviews that do not accurately reflect your customers' interaction with your products and services. Front loading product development with sound usability science is a defensive strategy. There is nothing like dropping a professional usability analysis on the desk of a leading journalist to keep him or her attuned to your commitment to solving the complexity problem. It will also make clear that you support his/her commitment to sound journalism, based on objective facts, not personal opinion.

- Usability science can bring new levels of insight to these complex marketing and product development problems. Use this powerful new science to define and solve the "complexity problem." In this regard, it is better to lead than follow.

* * *

Acknowledgements: The author would like to thank Mr. Paul Thurman, Professor Columbia University and President, Thurman Consulting, Inc., for his insightful comments related to the retail customer experience. The author also acknowledges Mr. Steven B. Katz (skatz@sbklabs.com), President of SBK Labs, for review of the various drafts and related comments. The author also wishes to thank Andrea P. Mauro (amauro@mauronewmedia.com), Senior Vice-President, Visual and Interactive Brand Development, MauroNewMedia, for her valuable assistance, including contributions to the content and structure of the overall article. The author also acknowledges David (david.miller@garamondagency.com) and Lisa Miller, Principals of the Garamond Agency, the author's literary agents, who have made substantial contributions to the structure of the new complexity problem. This article is an excerpt from the upcoming book by Charles L. Mauro, which deals extensively with the "New Complexity Problem" as a factor in achieving business success.

Notes:

1 Annual MauroNewMedia Product Complexity Survey, 2004

2 "Feature set" is defined as the total number of independent functions made accessible through the interface of the device that require independent cognitive processing on the part of the user. This definition does not cover the users ability to actually successfully perform rated features and functions since the skill acquisition demands of the device may be such that operational proficiency on the part of the user is not be possible due to poor interface design or skill acquisition limitations of the human information processing system.

4 Moore's law is the empirical observation that at our rate of technological development, the complexity of an integrated circuit, with respect to minimum component cost will double in about 24 months.

5 "Clients" in this context refer to actual traditional computers including desktops, portables, servers and related network-based CPUs.

6 "Ubiquitous computing" (ubicomp, or sometimes ubiqcomp) integrates computation into the environment, rather than having computers which are distinct objects. Another term for ubiquitous computing is pervasive computing

7 "Usability Science" (US): is a comprehensive research and development methodology driven by: (1) clearly specified, task-oriented business objectives, and (2) recognition of user needs, limitations and preferences based on theory and practice from cognition, psychology, group problem solving theory, business process modeling, operations research and network science and ethnographic research. Information collected using US is scientifically applied in the design, testing, and implementation of products and services. When applied correctly, a US approach meets both user needs and the business objectives of the sponsoring organization.

8 Hick's law, or the Hick-Hyman law, is a human-computer interaction model that describes the time it takes for a user to make a decision as a function of the possible choices he or she has.

9 Study conducted by MauroNewMedia in 2005 examined product development methods and best practices for 3 leading consumer electronics manufactures. The study included detailed analysis of structured product development methods and customer testing for a wide range of product categories.

10 Studies conducted by MauroNewMedia, Inc in 2004 and 2005. Each study focused on examination of front-to-back customer interaction segments for various high technology consumer products and on-line services. The study was conducted using a proprietary, structured methodology focusing on identification of customer interaction performance with in and across 32 interactive touch points ranging from retail store presentation to on-line delivery of goods and services. The study collected 250 data points for each segment based on a model combining cognitive workload, skill acquisition, satisfaction and brand attribute conveyance. Combined customer experience segments were modeled and compared to current Best-In-Class offerings.

11 'Random Walk" is a term of art in usability science where customers are observed resorting to random, undirected, button pushing in an attempt to obtain control of the interactive experience and related task flow. This is often a precursor to complete task failure including an inability to complete the task objective and related functions.

12 "The Upgraded Digital Divide: Are We Developing New Technologies Faster Than Consumers Can Use Them?"

13 "Why journalists should not proffer reviews on product usability and user interface design performance for complex high technology products and services." Summary: Critical analysis of the June 15, 2005 Business Week Online Product Review written by Steve Rosenbush titled "iTunes: Still the Sweetest Song."

14 Cost-Justifying Usability : An Update for the Internet Age, Second Edition (The Morgan Kaufmann Series in Interactive Technologies) by Randolph G. Bias, Deborah J. Mayhew (Paperback - April 4, 2005) Chapter 9: "Usability Science: Tactical and Strategic Cost Justification in Large Corporate Applications," by Charles L. Mauro. Pp. 265-295.