The elections in Iran are in full force, with only a few days left until the Friday ballot. Iranian television is filled with interviews with the candidates, sound bytes and advertisements about the vote. Movies are interrupted every few minutes by voting reminder message; in the middle of intense emotional scenes, bells ring and an animated ballot dances across the screen.

Candidates' Web sites tout the politicians' credentials and attributes, while blogs debate who is genuinely democratic-minded--or, conversely, true to the tenets of the Islamic Revolution.

The presidential campaign in Iran is short: about one month. There are a lot of rumors and discussions before the official start of the campaign season, but it really goes into gear once the Supreme Council announces the list of approved candidates. This year there are six. (For more information, see "Who Are the Candidates" on Open Democracy's Iran blog.)

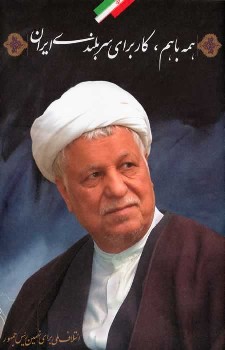

One of the candidates, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (www.hashemirafsanjani.ir), has done more than the others to market his particular presidential brand. In this brief article, I discuss the tools that his campaign has used to create the Hashemi brand.

Guerilla Marketing

Jay Conrad Levinson is often called the father of guerilla marketing. He defines it this way: "It is a body of unconventional ways of pursuing conventional goals. It is a proven method of achieving profits with minimum money."

While I cannot speak for the actual costs of the Rafsanjani campaign, the methods that the campaign is using are, indeed, unconventional. They are particularly unconventional for post-revolutionary Iran.

The Rafsanjani campaign has employed Iran's hip youth as its army of unpaid campaign workers. They wrap themselves in Hashemi stickers, tape his poster on their backs, celebrate soccer success in his name, attend performances at the candidate's Tehran headquarters and participate in skating events. They wear Rafsanjani campaign materials like fashion accessories.

This army of hip youth may be politically apathetic in large part, but that does not really matter. The Rafsanjani campaign has grabbed the image of youth and energy for itself. You might say that the Rafsanjani generation and the Pepsi generation are one. In other words, it may not matter to Pepsi whether the Pepsi generation drinks Pepsi, as long as Pepsi's sales are robust; similarly, as long as Rafsanjani wins the election, who cares who voted for him.

The Graphic Image

Rafsanjani is his own brand. Because of his uncommon looks, he is, arguably, the most recognized cleric in the world. As with every other candidate in Iran's presidential election, his image covers entire walls.

The campaign puts forth several images of Rafsanjani: the official site features a photo album that highlights his revolutionary achievements, while the popular photo-sharing site Flickr displays a very different view of the candidate.

The posters with his image are conservative and traditional, while the popular Hashemi sticker is really quite radical. On it, the Iranian flag is reduced to an abstract mark. His name, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, is reduced to Hashemi.

In a country where wives often call their husbands by formal names like Engineer (Mohandes) or Mister (Agha) and young girls are often called Young Ma'am (Dokhtar Khanum), the use of a name other than the surname is more than familiar: it is intimate.

With the plastering Hashemi stickers on ankles, across foreheads and on motorcycle windscreens, the Rafsanjani brand has come to mean that it is offering intimacy and friendship.

Will It Work?

Only time will tell how truly effective the Rafsanjani campaign has been. One thing is for certain: Political campaigns in Iran have changed. The Rafsanjani campaign is just one of the many signs of that change. (Check out the Flickr photo tag Election84 for a sense of this visual election.)

The campaign of former police chief Qalibaf, who is number two or three in the running, also targets the youth. With his casual and stylish clothes, chic glasses and sponsors such as Efes Zero Alcohol beer, the Qalibaf campaign directly competes with the Rafsanjani campaign for the hearts of Iran's youthful population.

The biggest difference between the two marketing styles is this: Rafsanjani's campaign is fueled by the images of teenagers and 20-somethings wrapped in Hashemi accessories, while Qalibaf's marketing team has chosen to make the candidate himself the symbol of youth with his new fashionable outfits and attractive image.

We'll Be Watching

It isn't just the presidential candidates who are seeking to brand and re-brand themselves--it's the entire country of Iran.

Plans are in the works for a tourism campaign that will target CNN's international audience. Payvand News reports that the country is ready for foreign tourists and investors.

Well, we'll be watching.